It all started at the end of last week with a tweet about Henok Mulubrahan and why he didn’t have a team for the 2022 season. Henok is a promising Eritrean cyclist who spent the last two seasons racing for the development continental team Team Qhubeka. In 2022 there was hope he would move to the top level with Team Qhubeka Nexthash. Recently, with the news that this team no longer has its World Tour license and will move to the third tier of professional cycling, Henok is left searching for a new team at the 11th hour if he wants to race at the World Tour or Pro Continental level.

The question posed was why such a talented young cyclist has not signed with a Pro Continental or World Tour team. Henok was written about across the cycling media in 2021 following his impressive second place at the Giro del Medio Brenta, sixth place at the Giro dell’Appennino, and a powerful performance in the 2021 World Championships in Flanders. And it is also worth noting Eritrea has recently delivered a string of high-quality young riders, and the re-signing of his compatriot Biniam Ghirmay by the Intermarché – Wanty – Gobert Matériaux team for 2022 should lead to an appearance at the Giro d’Italia, or maybe even the Tour de France.

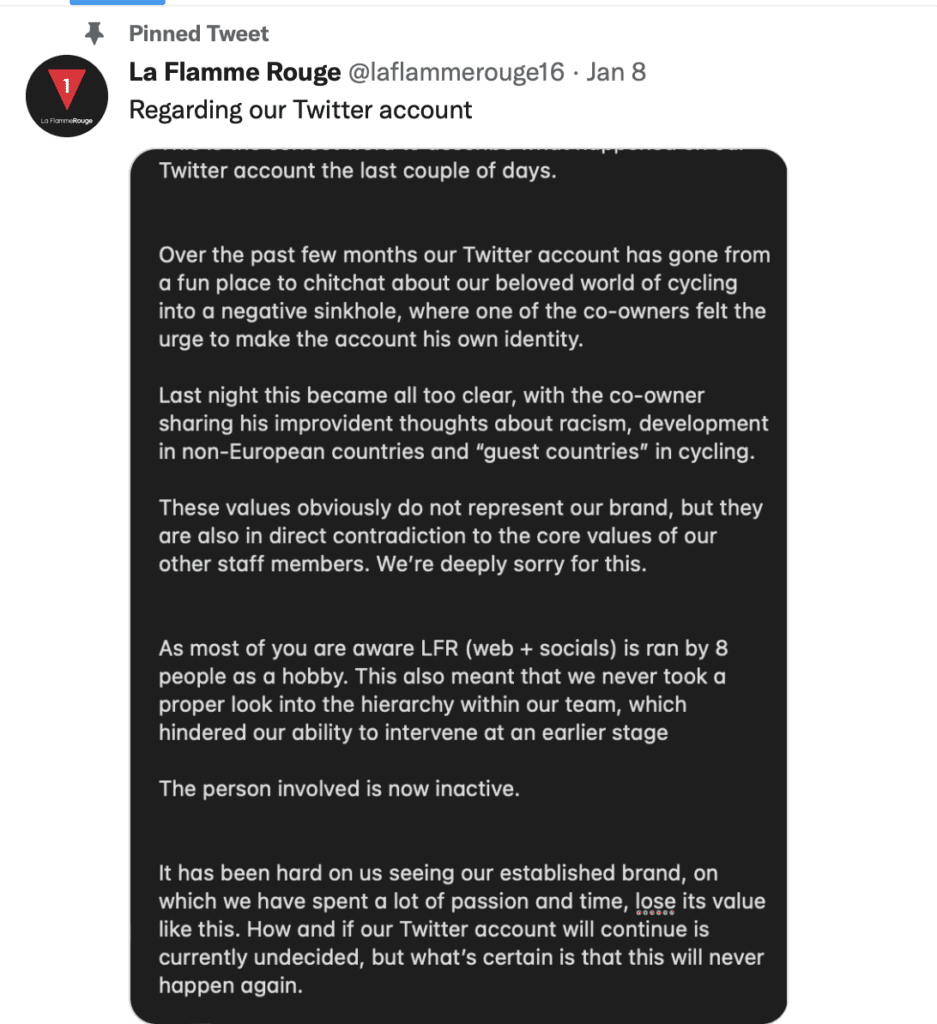

La Flamme Rouge (LFR), a cycling blog run by a group of eight amateur admins, jumped into the mix on Twitter with an incendiary tweet declaring there is no racism in the sport of cycling. If Henok was really as good as most people think, then his performance should speak for itself.

The naivety, ignorance, arrogance, privilege, or just lack of any empathy with the struggle for People of Colour (POC) in this was stark. The reaction from across the world was not unexpected, and in the last 24 hours, all relevant tweets have been deleted and a comprehensive apology issued by LFR. When you consider a sports blog posting this type of content with the focus on this topic over the last 12 months or so across many global sports already, including Soccer, American Football, Basketball, Athletics, and beyond. In that case, it is probably unforgivable, and we are glad that the person who published these tweets has been removed from any ability to use LFR’s social media accounts at all.

The reaction tweets came furiously from cycling ‘arm chair’ pundits trying to distill the lack of diversity in the sport of cycling down to one or two easy-to-solve issues, as Westerners tend to try and do all too frequently.

But this incident, and many others, including the Patrick Moster incident at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics on which we reported, lies a fundamental topic of why there are not more Henok’s, or in more direct terms, more African or POC riders in the professional peloton?

Firstly, I am a white, middle-class Westerner. I will never truly understand what it feels like to be a POC or to be a young athlete trying to make it in the sport of my choosing. However, I believe I have adequate ‘palmares’ to try and give a reasonable opinion on this topic.

I spent almost a decade living and working with young male and female African cyclists trying to break into the sport based in Rwanda. I have traveled across the continent with these riders. I have taken them to many editions of the Africa Championships and the World Championships and organized ground-breaking tours to the US, UK, and Europe. I have witnessed barriers to entry that are simply unimaginable to most and which break my heart on a regular basis. I have raised more money than anyone involved in African Cycling for these riders; found top-level coaches willing to work with these riders; negotiated equipment deals with the world’s leading cycling brands; constantly battled corruption at every turn; and never ever backed down when I encountered the consistent misogyny that still pervades sport and society.

Let us look at the data first: There are currently 1,316 riders signed to the 35 World Tour (18) and Pro Continental (17) teams licensed for 2022. Of these, nine riders hail from the continent of Africa, equating to 0.6%. For context, around 18% of the world’s population lives on the African continent. This simple data comparison shows Africa is under-represented in the top levels of the sport. What is even more worrying is that although eight of these nine are at the World Tour level, there is only one African rider across the 392 riders in the Pro Continental teams, where those destined for the top-level ply their trade. It is, of course, great to see four riders each from the two current powerhouses of African Cycling: South Africa (de Bod, Gibbons, Impey, and Meinjtes) and Eritrea (Ghebreigzabhier, Ghirmay, Kudus & Tesfatsion); joined by a solitary Ethiopian (Grmay) across the top two levels and we wish them every success in 2022.

Rather than writing a narrative about the challenges, I thought it best and most impactful to simply list every barrier to entry for an African athlete (of similar power/skill to a US or European peer) which I have witnessed, fought against, overcome, or lost out to, at one point or another:

- Equipment: Lack of access to basic equipment, minimal cycling infrastructure, virtually no cycling shops or distributors across the continent.

- Ineptitude of the infrastructure: Many of Africa’s cycling Federations are staffed with continually self-(re)elected leadership teams with little or no cycling experience.

- Education: Lack of educational structure for riders, leading to language difficulties also.

- Racism: Direct and overt xenophobia towards POC and African nationals.

- Cultural influences: Especially regarding women’s participation in sports.

- Visas: Difficulty in obtaining European visas from the same countries who colonized their lands.

- Lack of investment: Minimal cycling organized races at the national, continental level. No clear ROI from any of them, we assume, considerable funds flow from UCI, and every local Federation, to the Confederation of African Cycling (CAC).

- Employment: Lack of credible, professional teams on the African continent.

- Corruption: Another ever-present and unwanted European import to the continent.

- War, conflict, and historical challenges.

- Poverty: Limited electricity, drinking water, time to train and buy equipment.

- Lack of infrastructure: Poor driver awareness and ability, minimal safe tarmac roads.

- Representation: Who do these riders have to look up to in their sport?

Any one of these reasons could hinder a cyclist’s opportunity to ‘make it’. Many African cyclists I have worked with have faced almost every single one of these obstacles from the minute they got on a bike.

When Daniel Teklehaimanot and Merhawi Kudus were named in Team MTN-Qhubeka’s squad for their wild card entry in the 2015 edition of the Tour de France, it felt like there was a pivotal shift, was the door truly about to be opened for African riders?

On July 9 that year, I watched the race on a Macbook Pro, with a pirated subscription through a VPN network, at Rwanda’s Africa Rising Training Center with a dozen young Rwandan cyclists circled around the tiny screen. I will never forget the reaction and elation as Daniel took the KOM jersey, the first African cyclist to secure that jersey in the history of the Tour. I witnessed the skyrocketing belief level in each of those Rwandan riders. If Daniel can do this, so can they!

That was almost seven years ago, and belief is flagging once again. Not only do they not see black Africans winning jerseys, but they also do not see black Africans in the Grand Tours. In 2020, there were no black Africans in the Tour de France….the only POC of any nationality in the entire peloton was Kevin Reza of France.

The question of why aren’t more black Africans at the highest levels of the sport cannot be answered in 280 characters, nor in a back and forth with people who have never worked in the sport on the continent. We cannot fully answer it at Team Africa Rising, but we can shed light from our experiences with each and every one of the “reasons” listed above about why there are so few at the professional level.

We can continue to call on those apparently in charge of cycling on the continent to do better, to do much more. To demonstrate any ROI on whatever funds they have at their disposal. To demand more from the continually re-elected President of the Confederation of African Cycling (CAC) to show what African cycling could actually deliver if appropriately run by those who understand cycling and 100% focused on the athletes.

We at Team Africa Rising, and all our partners will continue to fight because of kids like Henok, Biniam, Fatima Deborah Conteh, Adrien Niyonshuti, Eyeru Tesfoam, Jean Claude Uwizeye, the rising stars at Lunsar Cycling in Sierra Leone, Masaka Cycling in Uganda, our friends in Algeria, Benin and Burkina Faso, and thousands more.

Over the coming days in 2022, we will continue to share our experiences, the cyclists’ experiences, and how we continue to have hope in the future of African cycling.